A Narrative for Nora: from the smallest of clues to an international life story

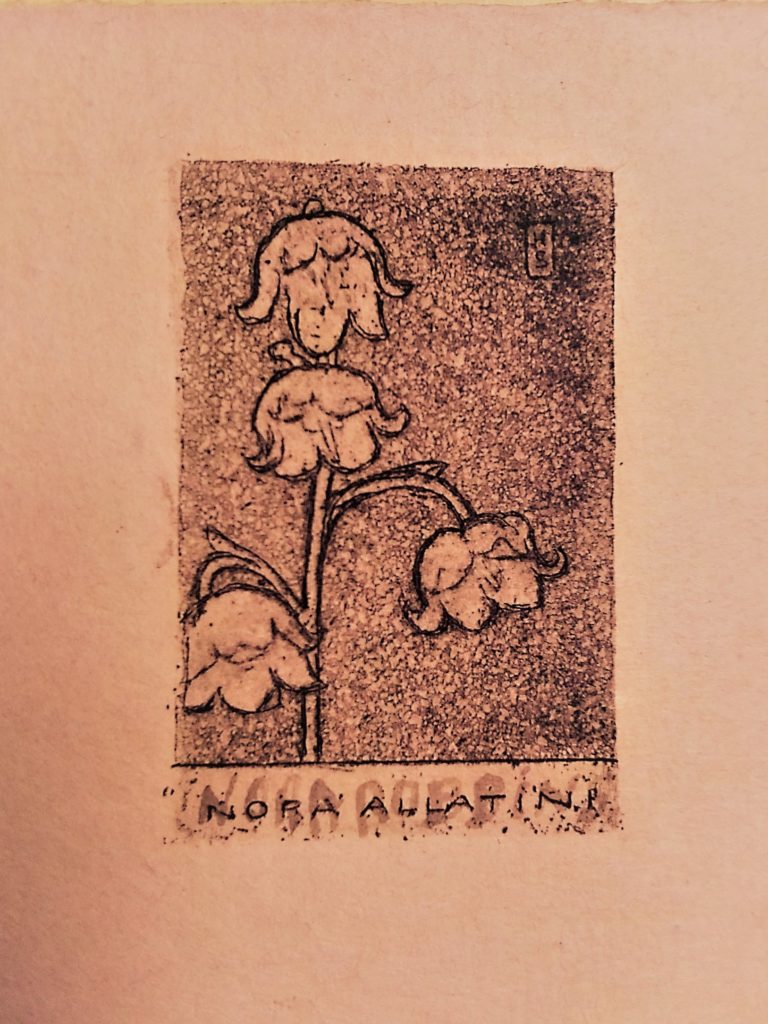

It was small…only around 5cm by 3cm, a little wonky-looking, and greyscale. Hardly the most ostentatious of signals, tucked away from view on the inside cover of a slightly battered looking book written entirely in French. What it was that drew the eye, and suddenly revealed the previously unnoticed double layer of text was a coincidence entirely down to the shape of a familial name. But there it was, sitting there, mysterious and quiet. The bookplate. A single flower, hovering over a dark background. The neat, angular lettering. Nora Allatini. And then, in faded ink, hand-written over the top, Nora Robbins.

It was small…only around 5cm by 3cm, a little wonky-looking, and greyscale. Hardly the most ostentatious of signals, tucked away from view on the inside cover of a slightly battered looking book written entirely in French. What it was that drew the eye, and suddenly revealed the previously unnoticed double layer of text was a coincidence entirely down to the shape of a familial name. But there it was, sitting there, mysterious and quiet. The bookplate. A single flower, hovering over a dark background. The neat, angular lettering. Nora Allatini. And then, in faded ink, hand-written over the top, Nora Robbins.

Who was this woman, Nora? And why had her book, obviously part of a collection valued enough to have been given bookplates, ended up here in the University Library? The catalogue gave away no clues. But librarians are not known for their acceptance of dead ends, or unanswered questions. With the interest of the team piqued, we decided to see what we could uncover.

We began with a simple historical search online. Marriage records led to birth records, they led to newspapers, to databases, and to books. Soon the great sweep of twentieth century history was before us, reaching across the European continent and beyond, taking in key events in history and touching on the lives of significant figures in the worlds of the arts, politics and the military… we were stunned. And so we had to share.

FROM BERLIN TO LONDON

Nora Meyer Cohn, it transpired, was born in 1889, the younger daughter of German banker and antiquarian Alexander Isaac Meyer Cohn and his wife Helene Dubs, and grew up with her older sister Lucy Esther (born 1883) in the Charlottenburg district of Berlin.

Alexander Meyer Cohn is most famously remembered as an autograph and book collector, whose collection was documented in a two volume sales catalogue in the year following his death. It contained well over 300 pages of listed autographs from across the world of politics, arts and culture; the Pall Mall Gazette reported the sales prices from the first day of the auction which included a letter from Napoleon to Josephine (2510 marks), a letter from Frederick the Great (1600 marks), the signature of Catherine of Aragon (1150 marks).

However, his collecting was merely one side of this charitable philanthropist. Throughout his life he demonstrated a dedication to the preservation of German literature and folklore. In 1889 he financed a museum for German Folk Costume, and over several decades he acted as treasurer for numerous societies and associations. An antiquarian of note, he is remembered as eschewing high society gatherings in favour of walking with his backpack in the Bavarian mountains. A biographer, writing after his death in 1904, described how “at the side of a finely-educated wife of Austrian-Polish origin, he found happiness in his home and was the loveliest father to his two daughters, and a wonderful host to his young and old circle of friends”, adding that he would make annual pilgrimages to the Goethe und Schiller Archiv (the oldest literary archive in Germany), to make speeches and present donations.

On 2 April 1910 Nora married Victor George Allatini, son of merchant Lazarus Allatini, whose family businesses in Salonika had provided his children with immense wealth and an upbringing in the fashionable London district of Kensington and Chelsea. The newly-married Allatini’s settled into a large 17-roomed marital home at 1 Lennox Gardens, Chelsea, where they had a household consisting of at least 7 servants, many from the continent. Nora’s sister Lucy had also married a Londoner, Albert Martin Oppenheimer, in 1906, and the sisters homes were not far from one another. In February 1913, Nora was presented at Court by her sister, in the Diplomatic Circle.

As Britain entered into a state of war with Germany in 1914 however, life would have changed dramatically for both sisters. Their German background would have caused both social difficulties and practical ones, with suspicion likely to have been levelled at them despite their marriages. Lucy’s brother in law Sir Francis Oppenheimer (with whom she corresponded regularly – their letters are now held at Balliol College, Oxford) was the British Commercial Attache at The Hague, but even he found himself on the receiving end of insinuations despite decades of loyal diplomatic service, with questions raised in Parliament in 1916 about his loyalties.

We have found little documentary evidence of either Nora or Lucy during the war years, but in late 1918, as the war drew to a close, Nora’s mother Helene passed away at her Berlin home. Whether Nora was with her we cannot from this distance of time know for sure, but we do know that Lucy, Nora’s sister, was there, as it was she who registered the death on the auspicious date of 11 November. Travel between Britain and Germany would have been particularly problematic during this time, and we have been unable to ascertain when Lucy travelled to her home country.

Helene Meyer Cohn, who died at the relatively young age of 58, had been a linguist, working as a translator of Polish, French and German for some of her country’s most well-known authors. Indeed, her translations of novels by Henryk Sienkiewicz and Władysław Łoziński continue to be held by German libraries to this day. A member of the Goethe-Bund of Weimar (a collective set up to bring together intellectual and artistic forces for the protection of the freedom of art and science at a time when these freedoms were under significant threat), it is probable that Helene was a major influence on her daughter Nora, whose social circles included artists and writers.

Sometime before 1917, Nora commissioned a piece of Meissen sculpture from artist Paul Scheurich. The resulting piece, showing “a lady surprised by the amorous attention of a Moor kneeling at her side” is said to be based on her. Initially produced as a limited run of three (one for Nora, one for the artist, and one to be held in the Meissen museum), the sculpture was exhibited at the Berliner Secession exhibition of 1917, and later reproduced in greater numbers for retail in the 1930s.

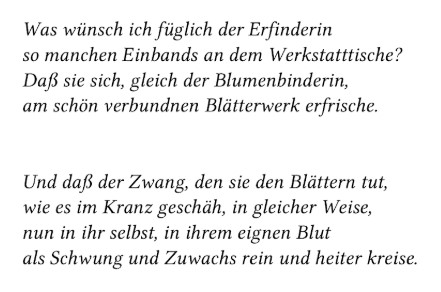

In around 1919, Nora found herself the subject of poetic musings from the pen of leading German poet Rainer Maria Rilke. Letters preserved in the British Museum testify to the personal relationship between the two, and the poem, which appears in several editions of the poets collected works, describe the writers fond admiration of Nora’s work with book bindings, describing her in flattering tones that allude to floral parallels.

Given her association with the German art world during the war years, it is tempting to speculate as to whether Nora, as a German-born woman, found it preferable to be there whilst hostilities were under way. Certainly, the climate of anti-German feeling in Britain may have made life here for her difficult. So far, we have been unable to locate any evidence for her living either in Britain or in Germany during this period, so this may remain a mystery. We have, however, ascertained that the bookplate which now sits, nestled inside decorative covers on our shelves, came into Nora’s possession while she was using the name Allatini, dating it to between 1910 and 1926.

This is because, perhaps unusually for the time, Nora filed for divorce from her husband in 1922, citing “restitution of conjugal rights” (meaning she claimed her husband was living away from her without a good reason). Speculating again, we could imagine that a separation during the war may have led to a breakdown in their relationship, but without evidence we cannot be sure. Electoral rolls show Nora with her husband at 1 Lennox Gardens in 1921 and 1922. Thereafter, from 1923 until 1926, she is listed as living at 11 Carlyle Square, Chelsea, alone or at least without enfranchised cohabitants.

In November 1926, a decree nisi was awarded, and the marriage was dissolved. On 15 January 1927, a mere few weeks later, The Times carried an announcement of her remarriage.

That Nora’s ownership of the book crossed the years defined by her marriages is clear from the dual names found on the intriguing bookplate. Aside from the names, the plate carries a simple, stylised floral image and, hidden in the background texture, a monogram of the letters HS.

Our research into this led to the German Jewish artist Hermann Struck, who was known for his etchings. Born in Berlin, Struck studied at the Berlin Academy of Fine Arts and in 1904 joined the modern art movement known as the Berlin Secession. He completed commissioned portraits of Ibsen, Nietzsche, Freud, Albert Einstein, Herzl, Oscar Wilde and other leading figures, but as a Zionist and Jewish activist he found his native Germany impossible to live in during his later life. Despite being a German patriot, volunteering for military service in World War I (from 1917 he was the referent for Jewish affairs at the German Eastern Front High Command), and being decorated for bravery, he emigrated to Palestine in 1922, teaching at Bezalel Academy and helping to establish the Tel Aviv Museum of Art.

Struck designed bookplates for many well-known figures, as well as for other members of Nora’s family – we have found auction records for bookplates designed by him which include one for her sister Lucy, as well as another design for Nora herself. In style and execution Nora’s bookplate is very typical of those Struck designed, and the floral motif links rather nicely back to the themes used in Rilke’s poem about her. Her patronage of Struck lends support to the idea that she spent time in Germany either during or just after the War, in the years when her first marriage broke down.

ENTER THOMAS ROBBINS

Nora’s second husband was Captain Thomas Robbins, the son of a Detective Inspector who had died during his sons childhood in Liverpool, who forged a remarkable military and commercial career. Born in 1893, Thomas Robbins came from an enlightened and modern family – his widowed mother brought up children who would make significant contributions to public life and gather honours in their chosen disciplines. His sister Rhoda, for example, became a science student, then principle of Swansea Training College, and won the prestigious Buck Scholarship to carry out research into educational practice at Bryn Mawr College in Massachusetts in 1928.

A veteran of the Great War, Thomas Robbins had served with the 6th Battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers, receiving the Military Cross for “an act or acts of exemplary gallantry during active operations against the enemy on land”.

Employed in civilian life by the Rio Tinto Company, he was no stranger to international travel. Before his marriage to Nora, he lived in Berlin with his first wife Elizabeth and travelled widely; their three children were born in pre-War Germany but passenger lists document his journeys to the United States and Gibraltar, as well as the UK. Married in 1918, Thomas and Elizabeth (Beth) Robbins, who herself came from a distinguished literary family (her step-grandmother, with whom she was exceptionally close, was Frances Elizabeth Bellenden McFall, better known as the feminist writer Sarah Grand), were parents to two sons and a daughter. Following their separation some time after 1924, the sons went to boarding school, and their daughter appears to have stayed with her mother. Their eldest son Patrick tragically died in 1938 aged 17, while at school, having accidentally poisoned himself. We have not as yet found any documentary evidence of a relationship between Nora and her stepchildren.

Following their marriage, Nora and Thomas Robbins lived together at 11 Carlyle Square, Chelsea, the four-storey townhouse she had moved in to following her separation from Allatini. Their neighbours at the time included the literary brothers Osbert and Sacheverell Sitwell at number 2, and the actress Sybil Thorndike at number 6.

In 1929 Thomas Robbins was appointed Managing Director of Silica Gel Holdings. Shortly before the outbreak of World War Two, he became involved in the National Coordinating Committee for Refugees as an assistant to Lord Hailey, where he organised the escape from Nazi-occupied areas of those who found themselves under threat from the regime. Whether his wife’s position as a German-born Jew or the time he spent living in Berlin in the 1920’s influenced this involvement we can only speculate, but it seems likely. Once war was declared, Robbins returned to military life as a Brigadier, albeit in a less front-line capacity.

From 1941 he was involved in the delivery of courses in civilian defence out of St Johns College, Cambridge, and travelling to the United States to gather intelligence and ideas at Charlottesville. February 1943 saw him appointed as the first Commandant of the Civil Affairs Staff Centre in Wimbledon, and on 17 December 1943 he was appointed Deputy Chief Civil Affairs Officer at the 21st Army Group (under Field Marshal Montgomery), a position he retained until 1945.

In the post-war years, Robbins was awarded a CBE, appointed to the Military Division of the Order of the Bath, received the Legion d’Honneur (at the grade of officer, for services rendered to France during the operations which led to liberation in 1944), and made a Commander of the Order of Leopold II by Belgium. He returned to his executive commercial activities post-war, travelling in the late 1940s to the United States and the Bahamas, where he would buy land on the Abacos on which to build a large home.

In 1939, Nora is registered as living at 22 The Boltons, a large property in what is still one of London’s most exclusive streets. In fact, this very house, with its 8 bedrooms, 6 bathrooms, 4 reception rooms and 100 ft garden sold in January 2018 for £40 million. Her household at the time consisted of a housekeeper, cook, parlourmaid, between-maid. She also had a visitor, Jan Weber, a Solicitors Articled Clerk. Twenty-two year old Weber had been born in Berlin, but avoided internment as an “enemy alien” (as records from the National Archives show) perhaps due to his association with the Robbins’.

Although information about Nora during this time is once again sparse, we do know that in 1936 she donated a gold ring containing an eglomise portrait minature of a man, made in around 1800, to the Victoria and Albert museum, in memory of her sister. Lucy Oppenheimer had passed away on 7 May 1935 in London, leaving Nora the sole survivor of her birth family. This ring is still on display today, in the Prints and Drawings Study Room.

Over the next decade Nora is listed on electoral rolls at various high-class addresses, including Rutland Gate in Knightsbridge.

Nora died on 20 December 1954, aged 65. At the time of her death she was living in a two bedroom flat at 32 Oakwood Court, Kensington, an upper class address where apartments today average at a value of £2.5 million. We have sadly been unable to locate any photographs of her.

We are awaiting a copy of her will.

THE BOOK AND THE BOOKPLATE

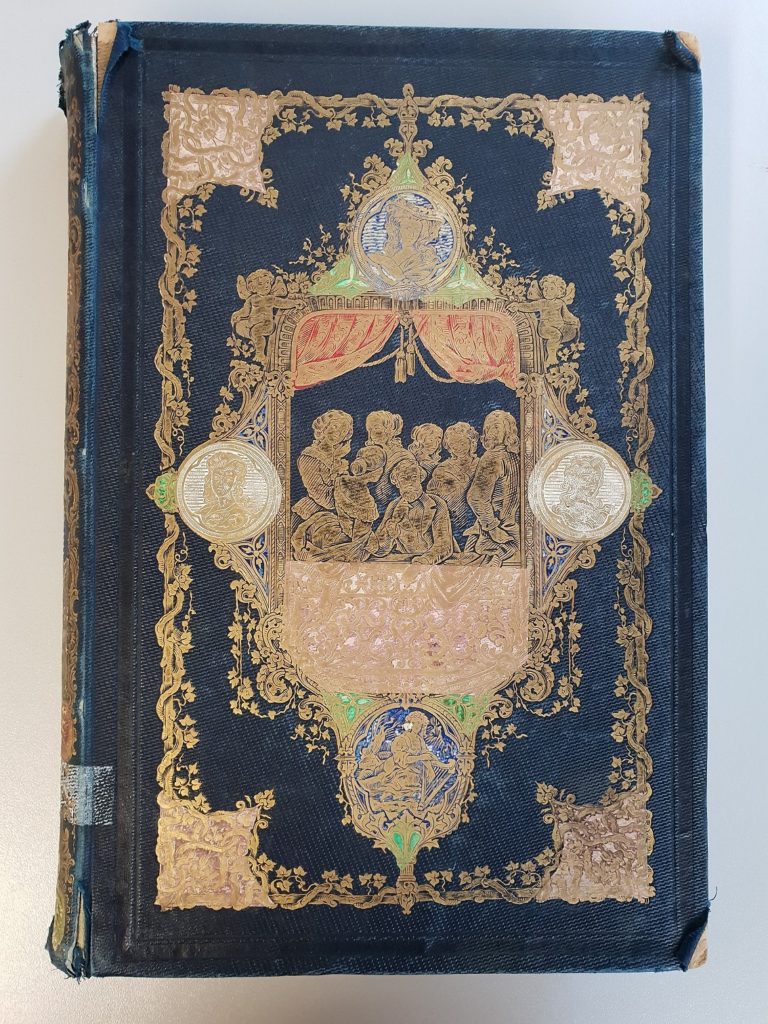

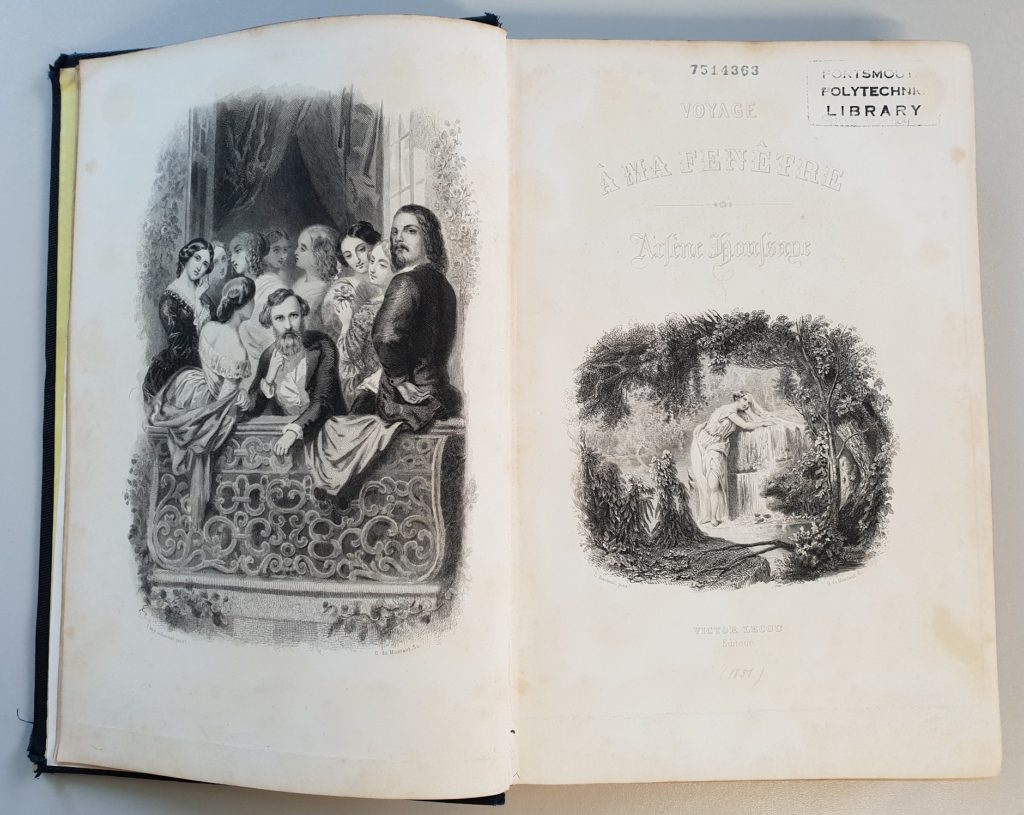

Nora was certainly not the only owner of “Voyage à ma fenêtre” by the French novelist, poet and man of letters Arsène Houssaye – it’s publication date of 1851 alone would suggest she was not the first to possess it. In the original French, and published in Paris, the heavily decorated tome is bound in gilded leather, and contains numerous fine illustrations. We could speculate as to how and why she possessed it – whether it came from the library of her father, whether she purchased it herself, or whether it was a gift, but we are unlikely ever to be able to say with any certainty that we know.

Nora was certainly not the only owner of “Voyage à ma fenêtre” by the French novelist, poet and man of letters Arsène Houssaye – it’s publication date of 1851 alone would suggest she was not the first to possess it. In the original French, and published in Paris, the heavily decorated tome is bound in gilded leather, and contains numerous fine illustrations. We could speculate as to how and why she possessed it – whether it came from the library of her father, whether she purchased it herself, or whether it was a gift, but we are unlikely ever to be able to say with any certainty that we know.

How the book she once owned came to rest upon our shelves also remains a mystery, with the acquisition information lost to time and the vagaries of cataloging. The accession number tells us it’s been part of our collection since at least the 1980’s, but nothing more.

Following Nora’s death, her widower remarried in the Bahamas in 1955, and eventually retired to the Isle of Wight where he died in 1981 aged 88. His third wife, Clare, died on the Isle of Wight in 2002, aged 96, and left a significant estate worth £1,864,556, most of which went to the Salvation Army. Perhaps this close geographical connection offers a possible explanation of how the book ended up where it did?

We may not be able to complete the provenance of the book, and many unanswered questions remain, but we feel privileged to have uncovered the remarkable story of Nora’s life.

-Paula Thompson

Sorry-should have said “Elizabeth was my wife’s grandamother”

Hello Stephen

Jonathan Webber, my cousin has already written. I am Jan Webber’s neice. My mother Paula was close to Nora all through the war and I would love to connect to hear more about “uncle Tommy.” I think the photo of my parents’ wedding has a photo of him and therefore perhaps a photo of Aunt Nora as well. There is a small woman standing next to Tommy whom I believe must be him

Thomas Robbins was my wife’s grandfather, Elizabeth was his mother, and this article pieces together so much of what we half knew. We have a half finished painting of the drawing room at 22 The Boltons with the walls hung with huge Flemish tapestries.

David Haldane Robbins ( wife’s father) went to Trinity, Cambridge and became European head of an American oil company and married into a Scottish military family full of colonial governors and colonels. We have several Struck works which we inherited. We would love to hear from anyone connected with this story.

This is indeed a fascinating story, and thank you for sharing it ! I have more than a passing interest and may be able to expand it as the young Jan Weber who stayed often at the Boltons was none other than my father. He certainly didn’t escape internement and was in fact one of the “Dunera boys” who were shipped to Australia. He spent 2 years there before Uncle Tommy’s connections got him a commision into the army, and job as a listener for British Intelligence. The reason he was staying there was because his mother Marie Weber was the daughter of Heinrich Meyer-Cohn, brother of Alexander. Before the war and his internment he was an articled clerk for Bertie Oppenheimer, brother of Sir Francis. Alas no pictures of Nora or Lucy or Uncle Tommy, but I have pictures of Alexander and Helene from the Heymann family archive in the Jewish Museum in Berlin. Jenny Heymann was Alexander’s mother. With kind Regards, Jonathan Webber

Hello Paula,

really great essay about such a little piece of paper! I’m myself studying Hermann Struck for some decades now and I never found that EX LIBRIS. Nevertheless, there are two more EX LIBRIS made for Nora by Hermann, even for her sister Lucy Oppenheimer.

What I wanted to bring into discussion: You are stating “A single flower” in this quite poor arranged artwork. But: The “single flower” is a Leucojum vernum which comes out to blossom in March and April. Have a look to google pictures for that great “spring runner”. Why is that “single flower” so important ? As you know, Nora had her wedding day with Victor George Allatini on April 2nd !!! Isn’t that the right day for Leucojum vernum ?!?!? Oh yes! All her life and library could be refaced with that tiny “spring runner” which obviously was made by Hermann right for the wedding day in 1910 ;-)) Do you agree ?

The two other EX LIBRIS came in 1914 and 1915 with a japanese theme: first the buddha Fukurokujoa with a crane near by (both signs of happiness) and second a little girl as Netsuke (also a sign of happiness).

I have another copy of this ex-libris, found in a book-shop in Belgium

What a fascinating story this is and well researched. I heard some of it told at our recent storytelling symposium and was keen to read up on it. Like everybody, I am drawn to this story from a personal point of interest which is partly the German and the Isle of Wight connection, partly Nora as such an independent woman.