75 years ago this week – our City in flames

75 years ago this week, our city was a very different place.

Resources held in the Library can help us to find out more about the history of the City, and place them within the local, national and international contexts of the War. To create this post, I have used the Records of the Corporation of the City of Portsmouth (942.2792/POR), a selection of our books on the history of Portsmouth, and the website of the Imperial War Museum. While our local history collection is not extensive (the public library has a whole floor dedicated to it by comparison), it is an important reminder that we are part of the city, and the events which shaped the city had a hand in shaping our institution too. Indeed, the site on which our Library sits was once occupied by Government House, lost to German bombing in October 1940.

There was a time when everyone in Portsmouth knew what happened on the 10th January 1941. Even amidst the horrors of irregular but frequent air raids, this date brought with it a new level of death, destruction and heartbreak. For the people of the city and the surrounding area, it was a night which would not easily be forgotten.

On this one night, hundreds of German planes dropped 25,000 incendiary devices and hundreds of high explosive bombs onto the city below over a seven hour period. The first bombs fell at around 7pm, on the electricity station. That this and the water mains were the initial targets lead many to speculate as to whether the pilots knew the city. Without these two utilities, the people of Portsmouth were almost powerless to prevent the inferno which ensued, during which 2,134 fires were reported.

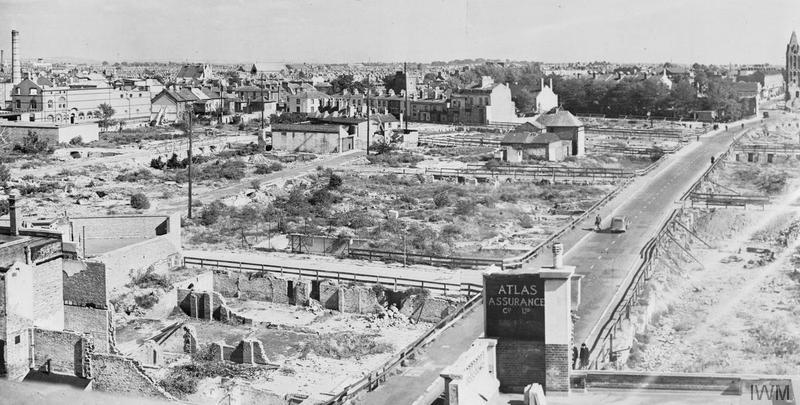

The raid destroyed the major shopping centres of Commercial Road, Palmerston Road and Kings Road. The Guildhall, standing tall in its original Victorian glory, fell victim to three incendiary devices. The third of these set the building alight, creating a beacon for the pilot of another plane who then deposited the high explosive which would collapse the roof and lead to the complete obliteration of the buildings interior. Other buildings wrecked included six churches, the Eye and Ear Hospital in Old Portsmouth, part of the Royal Hospital, Clarence Pier, the Hippodrome theatre and three cinemas, the Dockyard School, the Connaught Drill Hall, the Central Hotel, the Royal Sailors’ Rest, and the Salvation Army Citadel in Lake Road. The FA Cup – won by Pompey in 1939 – was later dug out of a Bank in Commercial Road, where it had been placed for safekeeping.

Over 3000 people were made homeless in this one night.

171 people were killed, 47 of them in an air raid shelter at Arundel Street School, which took a direct hit. 430 people were injured.

Speaking to the public through the local newspaper, the Lord Mayor Mr Daley said the next day:

“At last the blow has fallen. Our proud City has been hit and hit hard by the enemy. Our Guildhall and many of our cherished buildings now lie a heap of smoking ruins. To you all, however, I wish to pay tribute to the splendid manner in which you have stood up to this violent calamity, and especially I should like to thank all those members of the public services who stood to their jobs, as I knew they would do…We are bruised, but we are not daunted, and we are still as determined as ever to stand side by side with other cities who have felt the blast of the enemy, and we shall, with them, persevere with an unflagging spirit towards a conclusive and decisive victory. To you all, therefore, I say what I feel you would wish me to say – keep a stout heart, keep your chins firm, and your heads high. Be calm, be steadfast, be firm. Now is the golden opportunity for you all to exercise that spirit, which is to us all, the essence of our struggle – the spirit of comradeship and mutual help.” (Blanchard, 1945, p.184)

When the Council met on 14th January, the Chairman of the War Emergency Commitee said that “the most remarkable thing was that on the morning after the raid, the City was carrying on very much as usual”. That, he said, was “not due to accident, but to the extraordinary way in which reinforcements arrived, to the great help of the fighting forces, and to the foresight of the Council” (Blanchard, 1945, p.184)

Carrying on very much as usual would have been a feat indeed worthy of remarking upon given that people in Southsea were being warned to boil drinking water for 10 minutes to prevent the potential spread of diseases such as typhoid, and until arrangement could be made with the dockyard, electricity supplies remained cut off.

On 17th January, a week after the raid, a mass funeral was held in Kingston Cemetery. Attended by local dignitaries and representatives from the armed forces, the ceremony included an address by the Bishop of Portsmouth. Images of the cortege passing through the bombed streets on the way to the cemetery are a reminder of that grim determination to “keep calm and carry on”. Today, a memorial marks the place where these people rest.

It was the thirty first air raid which had been made on Portsmouth during this war. Many more were to follow, resulting in the destruction of over 10% of the entire cities housing, damaging the same number again, and causing the deaths of over a thousand people, most of whom were civilians.

Much of the locality around the Library and indeed the wider campus area was shaped directly by the events of 1940-41. Post-war development was to a large extent determined by the patterns of bomb damage, and many of the landmarks we now pass by and take for granted were erected in place of those lost to the air raids. If you look around, the scars of war are still there to be seen. Leave Ravelin Park by the entrance to Ravelin House, for example, cross the road, and look up at the walls of the City Museum outbuildings. There, in the red and brown brickwork, you’ll find the shrapnel damage of those long nights, still there, still touchable.

Blanchard, V (Ed.). (1945). Records of the Corporation 1936-1945. Portsmouth: Grosvenor Press.

My great aunt was one of the victims along with her husband killed in the direct hit on the air raid shelter in Arundel Street school, her name was Florence Maude Stemp/Nee Lake and her husband was called Harry Stemp, I remember my grandmother and mother talking about her and her husband and apparently they owned a fish and chip shop nearby possibly in Arundel Street, not sure ? Also not sure where she is buried with her husband maybe in Kingston Road Cemetery, how can I find out if they are buried in the cemetery if someone has nicked the bronze plaque??? What is wrong with people

Hi Guy. Your message is near on 19 months old, but my great grandmother, aunt and one other relative are on that list too. Caroline, Lily and Ethel Cooper. My dad used to talk about it. He was 9 at the time. They are all buried in the communal grave as far as I know.

There is a photo of the service held at the mass grave. It’s been posted on Facebook and it might be a Portsmouth News photo.

My Father Antony (Tony) Alfred Bushby was a projectionist in one of the cinemas that was bombed. He had scars on his back from the bombing which he stated took a direct hit. He went on to serve in the Royal Navy during the war on HMS Searcher an escort carrier. His brother Gordon C Bushby having been killed during the war is memorialized on a marker I believe in either Portsmouth or Worthing where they were raised. My father passed away almost 2years ago at 98…A member of the greatest generation…..

Is there any records of a house in finsbury st Portsmouth being damaged by incendiary bomb which my parents lived in.

Writing this the day before the 80th anniversary in 2021, I am struck not only by the loss of life but the detail that the author has uncovered.

The Commonwealth War Graves site records the names of many of the dead that are buried in the Borough Cemetery, often with details of their address and place of death. Combining the research above with the CWGC data builds into a fascinating picture.

Where is the memorial for the common grave. I am Portsmouth born and bred but not aware of this till now, can you help.

Hi Anne

The grave is in Kingston Cemetery, but I’m afraid I’m not sure of the exact location within the grounds.

Try asking at the cemeteries office in milton cemetry. They have the records and are very helpful.

It’s on the path next to railway track about half way down

A four-panel memorial in Kingston cemetery has all the names of the civilian war dead except three who are listed as Unidentified. the memorial was attacked a few years ago and the very sizable bronze plaques listing the names were stolen.

Many thanks – fascinating read. Now I’m wanting to come back to POrtsmouth to re-look at some things with a critical eye! [LIke, say, the Museum walls!]

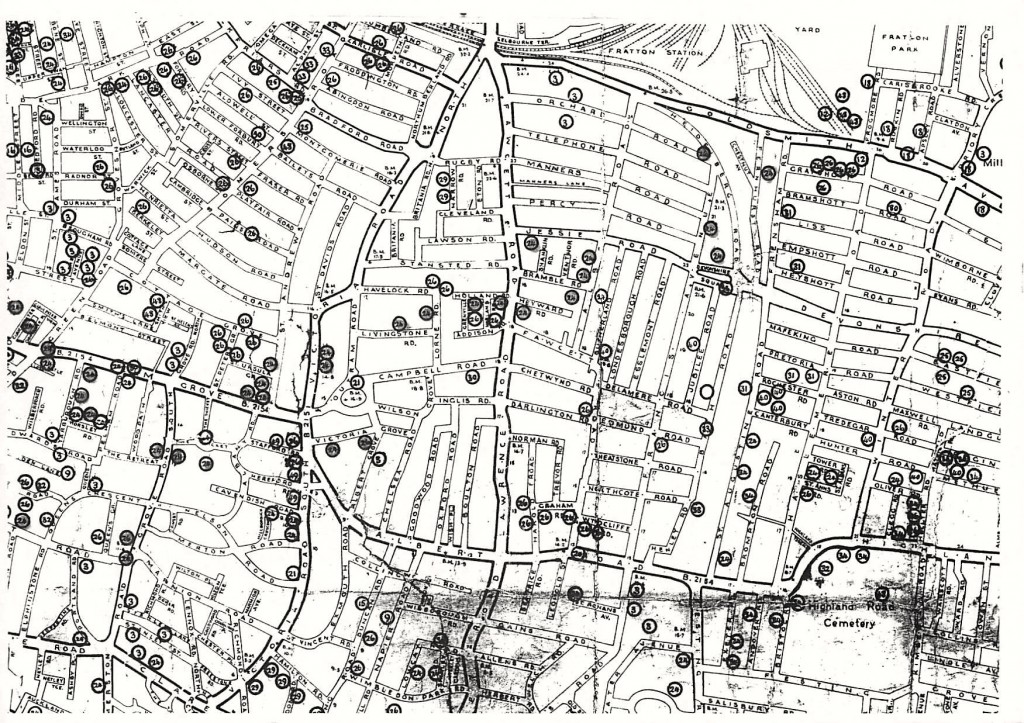

Is there an online full version of that map?

The bomb map is held by the Local History Centre in the Central Library, Guildhall Square. There are various images of parts of it circulating on Google (search for Portsmouth bomb map), but they are of varying quality.

hi, wonderful article!

Quick question regarding the bomb map. Have you got a reference?

Thank You

Hi Fern, the bomb map is held by the Local History Centre in the Central Library in Guildhall Square.

This is a fascinating piece of research. I have heard of these events from my parents and I shall be showing them this at the weekend. Nice work Enquiries!