Emotional education

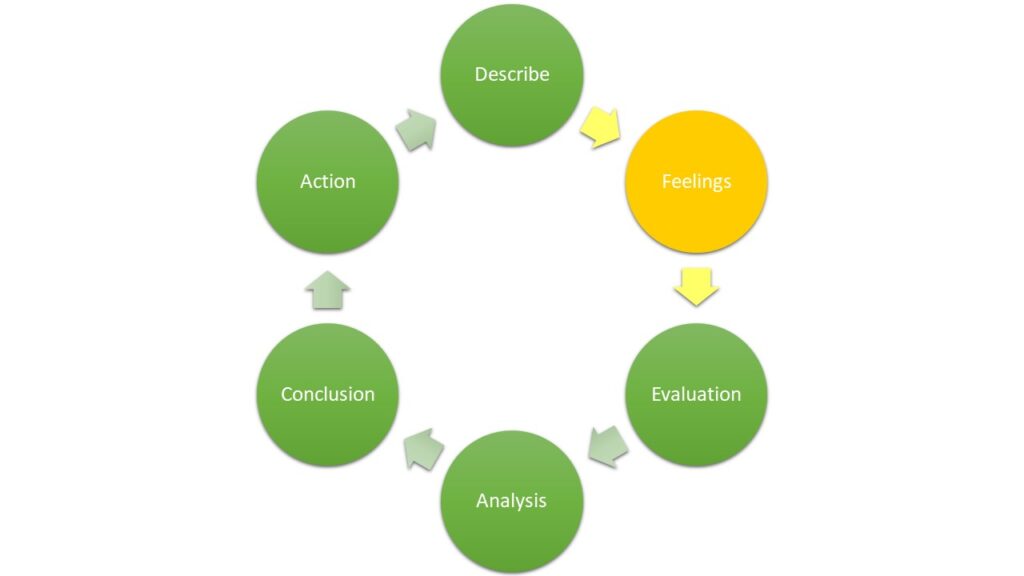

It should concern us that the focus of scholarship since its inception has been to purge thought of emotion, to exclude the body and to build fortresses of investigation and conjecture in the rarefied and arguably imagined space occupied by philosophy and theology, from which all our modern academic subjects derive. We have come a long way since Descartes attempted arbitrarily to separate body and mind in stark contrast to all Eastern philosophy, and yet so many of us are still used to learning without engaging fully with our feelings. Another warning bell begins to ring when we consider how Gibbs famously considered our emotional processes and reactions to findings in his development of Kolb’s earlier experiential learning cycle to describe a truly integrative reflective process.

Gibbs’ reflective cycle

Gibbs recognised that if we ignore our feelings, they are likely to re-emerge disguised as intellectual arguments. Better by far to be honest and separate thought from emotion, to reflect on the origins of both, and hold both as valuable avenues of enquiry. Sadly, emotion has been viewed since the Enlightenment as an affliction affecting women: something to be kept out of the male-dominated world of scholarship. Things are changing now but old prejudices die hard (McVitty, 2022).

Gibbs recognised that only by understanding how we feel about something can we respond with integrity and authenticity. It is true that extreme emotion often breaks down our ability to communicate clearly, but this usually stems from not being able to express ourselves so that emotions build up to bursting point. Expressing emotion continuously and skillfully is a life skill that we should all cultivate, and it is now finally being recognised that has a place in education. Furthermore, emotional expression helps bring teachers and students closer together, creating productive and supportive relationships that excite learning and foster empathy and inclusion (Moss, 2022), and so should, at least in theory, help more lecturers bite the bullet and pursue a decolonised and more inclusive curriculum.

This change poses serious challenges. It requires responsibility and emotional maturity and might lead staff and students to discover things about themselves they do not necessarily like. This is no bad thing: recognising what is unsatisfactory is necessary to change it. It is not easy, though. Is it not comfortable. And in the case of many subjects, particularly the natural sciences and philosophy, it arguably runs contrary to thousands of years of scholarly tradition. Still, these are living disciplines, and the one constant of all living things is that they are in a constant state of change.

References

McVitty, D. (2022, May 23). It’s reasonable to expect universities to practise emotionally literate pedagogy. Wonkhe. https://wonkhe.com/blogs/its-reasonable-to-expect-universities-to-practise-emotionally-literate-pedagogy/#

Moss, A. (2022, May 23). The connections we make with students could be as important as the pedagogies we adopt. Wonkhe.

https://wonkhe.com/blogs/the-connections-we-make-with-students-could-be-as-important-as-the-pedagogies-we-adopt/

Leave a Comment (note: all comments are moderated)